Introduction / My Thoughts on the Royal Navy / Chapter 1 - Early Navy Days / Chapter 2 - H.M.S. Hood / Chapter 3 - Portsmouth Barracks / Chapter 4 - H.M.S Cossack / Chapter 5 - Coastal Forces / Chapter 6 - H.M.S. Skate / Chapter 7 - H.M.S. Tarbert / Chapter 8 - H.M.S. Concord

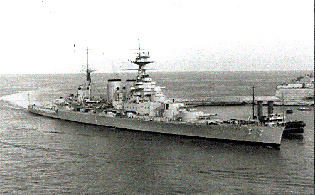

Chapter 2 - H.M.S. Hood

Launched: 1916

Commissioned: 1920

Displacement: 42,000 Tons; 46,300 Tons loaded

Four turbine engines producing 144,000 HP

Top speed 31 knots plus

Fuel capacity: 4000 tons

Length 810 feet

Beam: 105 feet

Draught: 30 feet

Main armament: 8 x 15” guns

Secondary armament: 12 x 5.5” guns

Four 21” above water torpedo tubes

Two 21” under water torpedo tubes

Crew of 1200 plus

I joined her in September 1936 and left in November 1939

Shortly after this I was drafted to H.M.S. Hood, my first ship. The Hood was in Portsmouth Dockyard after having been given a minor overhaul and would be going to the Med. as flagship to the Battle Cruiser Squadron consisting of H.M.S. Hood and H.M.S. Repulse

The Royal Navy had at this time three battle cruisers the Hood, Repulse and Renown of these Hood was of a class of her own, the other two were sister ships At the start of WW II Hood and Repulse were but for a few modifications no different to their original construction, they were built as fast gun ships and this meant that there was a lack of armour decking, This may have been the cause of Hood’s sudden sinking while in action against the German battleship Bismarck. Bismarck at that time was the most modern battleship in the world she was on her first sortie against our convoys having just left the ship yard were she was built

Bismarck left the area after the battle and for several days avoided the Royal Navy finally being found, brought into action and sunk, her first and only sortie lasting about seven days

The Renown had before the start of hostilities been given a complete overhaul, this had taken over two years to complete. The overhaul meant that except for the 15” guns, every thing else was stripped from the hull and the ship fitted with new boilers, engines, modern guns, extra armour protection and modern superstructure. When Renown rejoined the fleet she looked nothing like her sister ship Repulse but proved her self through out the war.

Before joining the Hood we had to be given medical examinations, not very severe, and injections for various known infections, we were also issued with pith helmets which we never wore.

Then came the day, 8th September 1936, all our kitbags and hammocks were loaded onto lorries to be sent to the ship, then around six to seven hundred sailors of all types were marched from barracks to the dockyard headed by the band, we were on our way.

On the quayside waiting the drafts were the regulating and supply staff that gave out the messing arrangements and I was allocated a mess that would be my home for over three years.

The next day we had to fall in at the Engineers regulating office which was responsible for the activities of all Chief, PO, Leading and 1st and 2nd Class Stokers and the allocation of duties to us 2nd Class Stokers emphasised how undermanned the navy was. In normal commissioning of ships all 2nd Class Stokers would be allocated for various boiler room duties which in itself covered most of the heavy dirty work, boiler cleaning, cleaning uptakes that takes the furnace fumes up to the funnel and boiler room watch keeping duties. Other work consisted of cleaning fuel tanks and double bottom tanks which gave extra buoyancy to a ship.

When my name was called I was told that I would work in the centre engine room, this was because there was an abundance of us new stokers and not many experienced stokers. During my time on the Hood I never once worked in the boiler rooms.

Starting our duties in the engine room began with cleaning up after the minor refit, the brass work was all tarnished, the handrails of steel were all rusty and the plates of the walking platforms very dirty. We worked hard getting the engine room up to a presentable state. Also as the ship was on a new commission the ship had to be stored not only with food but many spares that were required to maintain the ships’ many mechanical appliances. Later the ship had to be fully ammunitioned, quite a task with the armament of 15” and 6” guns, many anti air defence guns plus torpedoes. It was quite a work up before we went out for engine trials. When at sea us engine room staff would be in three watches for duties so that there was always someone tending the engines and recording all telegraph movements. Two of us would be in the well tending the various steam auxiliaries, one of the stokers on the starting platform would man the phone and keep the log while another stoker would be responsible for taking all man bearing temperatures and the torque of the two outer shafts passing through the engine room, these shafts being driven by the two turbine engines in the forward engine room.

I never did a watch in the forward engine room though I often had a watch in the after engine room which was the turbine for the starboard inner shaft, the centre turbine was the port inner shaft. In the after engine room was the steam engine for the steering gear, this engine did a lot of work because as the wheel in the wheelhouse was turned the engine had to give instant reaction to the rudders.

After some weeks of preparation and trials it came the time for us to proceed to the Med, this journey taking three days for the nine hundred mile trip in which time we were always doing some exercise to get the ship company into a fighting unit. It was the same every trip always doing war exercises whenever ships of the navy were on passage. Action stations would be sounded and all personnel would make haste to their allotted action station; mine at this early stage was centre engine room on watch, after damage control off watch and 6” ammunition supply longest off watch. By doing this in a watch system the running of the ship was not interfered with.

Before reaching Gibraltar, our first port of call, I was taken sick and confined to the sickbay with Quinsy, an abscess in the tonsils. The Surgeon Commander had me taken off ships food and I was provided with a diet cooked by the Captain’s chef, I went back to the ship’s cooking after about three days, worst luck and a few days later returned to normal duties. My first views of Gibraltar were through the sickbay portholes.

It was decided that all the ships companies’ oilskin coats would be stowed in a compartment below the foreward mess’s as these would not be required in the Med, this was convenient for us as we did not have to use our locker for storage. But alas on our return for the Coronation the oilskins on being brought out were one sticky mass, the heat in the compartment had melted the oil base and the oilskins had stuck together. Every one of the crew had to be supplied with a new oilskin.

The Hood stayed in Gib for quite a few weeks before sailing for Malta our main base. One of the first tasks that was always done on Navy ships on arrival in port was to refuel. At Gib the Hood always berthed on the mole an extra long breakwater that made Gib an excellent harbour. Fuelling was done by way of gravity fuel tanks inside the Rock; this was a very slow process as the Hood would require some three thousand tons of fuel and the operation would take many hours. If fuelling was required urgently then a fleet tanker would be used.

I did have a few days looking around Gib when off duty, the swimming at the back of the Rock was excellent and we always returned to the mainstreet for shopping and the few bars before returning to the ship.

Before proceeding to Malta we went over to Tangiers in North Africa, an International port, for several days. I did manage to go ashore for a few hours, the first time I had been on foreign soil, other than British territory. Us new sailors were given the advice by older hands, that on arrival at the jetty to stay in groups at all times and pick one of the locals who for a fee would show us around. This was good advice as it was found by some individuals that to be on your own there was always the chance of getting molested.

On leaving Tangiers we then went on to Malta carrying out exercises at all times. The trip to Malta was very pleasant and with a calm sea all of us ex Drake class were looking forward to the place that was to be our main base for three years.

We entered Bigha Bay and were between two buoys facing towards the sea opposite Valetta Customs House and in front of Bigha Hospital, except for a short spell later in the floating dock we were always moored in Bigha Bay. On this our first view of Malta we were astounded at the vast number of churches, many of them with their bells ringing as one old hand remarked, ‘the land of hells, bells and terrible smells’.

During our many visits to Malta we who wanted to took tours to the many bays and enjoyed the sights and the superb swimming. The nightlife in Malta was very varied from cinemas to numerous bars and some nightclubs, though in my early days I was restricted to evening leave only.

It may be best at this stage to stay with my early training on the Hood. The normal routine would be for a second-class stoker to be uprated to first class after one year; thus all of us from Drake were rated accordingly. We spent some evenings at night school preparing for our Education Certificate which was required towards promotion. My time was spent on engine room duties and main watchkeeping at sea. In harbour we had our round of duties to do in the evenings, these would be any one of numerous tasks. We would be given duties such as fire party, engineer’s office messengers, assisting in the various chiefs and PO’s messes, helping the messman, perhaps having to keep the bathrooms clean along with the passageways for evening inspection by the officer of the watch, these were the normal ones. Sometimes there was a need for stretcher and store parties. Later on we would if required do shore patrols; I never did this during my time on the Hood.

After I was rated first class, which brought with it an increase of pay, seven shillings per week, the Stoker PO in charge of the centre engine room gave me the job of being Chief Engine Artificers mate and this proved to be very helpful to me. Chief Herring was an exceptional person, his main duties being to ensure that the engine room was always in a state of readiness for sea, he was responsible for all the machinery and during my time with him my education was greatly advanced. Chief Herring would explain every thing he was doing and what the action of any piece of machinery was. When I did my POs course the Chief’s words were a great help.

Chief Herring had been called up during World War 1 and had decided to stay in the Navy afterwards. He told me how in the first months at sea he was still in civilian clothes. His wife had come out from England and was living in Malta and every evening when possible he would go ashore and I always remember that he always brought me back a raw fig, which I looked forward to.

It was Chief Herring that gave me the taste for rum. The Navy had finally realised that the Chief should not be at sea because of his age and it was decided to put him ashore and return him and his wife to England. On the day he was leaving I was working with another chief when Chief Herring called me up from the engine room to say goodbye. He then took me to his mess and duly poured out his tot of rum for me saying ‘that’s yours nipper, you are a good lad, drink it down,’ we shook hands and said goodbye and that was that,

I then went to my mess as it was dinner time, midday, I had my meal and suddenly felt very weary, I slid off the stool under the table and went to sleep, waking up several hours later with a liking for rum!

Prior to my time with Chief Herring I had requested to do the auxiliary watchkeeping course and shortly after the Chief left I started the course. The course consisted of extensive working with the auxiliary machinery and passing on examination on each machine. This type of machinery was always in use and was vital for the running of the ship in harbour or at sea.

There were three types of dynamo engines; steam turbine, steam reciprocating and diesels, twelve in all, there were the horizontally opposed steam engines that supplied hydraulic power to the main gun turrets, also there were the evaporators that supplied fresh water to the ship.

The evaporators were not very efficient as they took seawater by pump into a batch of coils inside the casing. Steam ran through these coils heating the seawater surrounding them, the steam from the seawater was condensed into pure water and pumped into the ships water system, pure water being required for the ships main boilers. There were two ways of testing for pure water, one being that as the fresh water was being pumped away through our electrical circuit if the water was not pure a light would come on, electricity will not pass through pure distilled water, the other test was quite simple a phial of water was taken to which was added two drops of silver nitrate, if the water was not pure a cloud would appear in the phial.

There were also the refrigeration plants that came under this training; two types being in use, Calcium Chloride and Ammonia.

The last of this course was the many motorboats aboard the Hood; Admiral’s Barge, Captain’s Motor Boat, Squadron Engineers Captain’s Motor Boat and two motor launches each with a capacity for 50 persons.

When one had completed training on this course a certificate was issued and the person’s records sent to RNB for entry on the POs list for further training.

I had at this time about eighteen months in the Navy and had a very good start to the promotion list.

This part having covered my training days I have to go back to my early days on the Hood to recount some of the incidents that are always in my memory. Things may not be in chronological order, as we were forbidden to keep diaries.

One early incident involved a theft of money from a ditty box, a wooden box supplied for ones personal effects such as pen, paper, photographs and intimate objects. A sum of money was missing and it was reported to the regulating office who did an investigation but got nowhere. A few days later my friend McGinley saw a stoker go to a ditty box and noticed that it was a different box to one this stoker had previously gone to, on checking up the first box was the stoker’s but the other box was identified as the one where the money was lost from; it was identified by an ink stain on it. On the facts being presented to the stoker he admitted the theft and after doing a prison sentence was discharged from the Navy, he was only caught because of an ink stain.

In April 1937 the Hood paid a visit to Gulf Juan on the French Riviera and it was arranged through ‘Thomas Cook’ that there would be a tour up to Nice then to the casino in Monte Carlo with a run up through the hills to Grasse and back down to Antibes to Gulf Juan. Us under 20s, if we went, were allowed all night leave which we took advantage of, this trip was not very expensive and thoroughly enjoyable, there was also a lunch provided. At Grasse we visited a scent factory and the girls delighted themselves by spraying us with neat perfume and as we were still in our serge suits the scent hung around for many months.

The Spanish Civil War had started in 1936 and the Spanish warships were interfering with Merchant ships of all nations. The League of Nations decided that warships of various nations should patrol Spanish waters on non-intervention patrols to protect shipping.

The Hood on her patrols would call at Palma in the Balearic Isles and operate from there. Majorca being under Franco’s insurgents. We would run between Gib, Majorca and Malta; this run was carried out many times.

Once when at anchor our Admiral who, when ever possible took the dingy away for rowing his keep fit exercise, collapsed in the dingy and had to be recovered by the watch on deck. It was very unfortunate for the Admiral as he through his illness was put on the retired list, though when the war started he was brought back to the Admiralty, he served through out the war, his expertise in gunnery being very valuable

In 1937 the Hood with the Med Fleet sailed into the Atlantic to do war exercises with the Home Fleet. During these exercises we ran into very rough seas and severe storms, up until then I had never encountered such heavy weather. Nearly every ship in the two fleets was damaged and nearly every ship lost its sea boat.

To describe a seaboat; every ship has one boat ready for lowering into the water. This boat, which on a large ship would be a cutter and on a smaller ship a whaler, if the pipe was away seaboats crew then the watch on deck would man the boat, but if the pipe was away lifeboat, any man near the boat would be used as a matter of urgency. I was involved in one such incident on one of my later ships.

After the fleet exercises the Hood was called back to England for the Coronation of King George VI. This was a welcomed break as we were in England for a few months.

We arrived in the Solent and came in through the Needles. I believe it was the only time the Hood ever did this. The crew enjoyed a bit of home leave and after the inspection by the King of the multi national ships there was dispersal to all parts of the world.

The Hood had some repairs done and it was decided that she would do a full power run before returning to the Med. This was done away from land as the wash caused by her wake would do a lot of damage if too near the coast. We had worked up to top speed when we went over a sand bank and our circulating pumps pulled the sand into the steam condensers and split the inner tubes. This allowed salt water to enter the boiler water system and laid the ship up for several weeks for cleansing and repairs. This was a bonus to us as it kept us in England a bit longer.

The Hood eventually left and called at La Rochelle on the way to the Med. Leave was given and several of us went ashore and had a good look around the town and then went to get a meal before returning to the ship. This was awkward because of the language problem; we did manage to get a meal by going into the café’s kitchen and pointing to what we wanted. The only thing wrong was that the meal was cooked with heavy garlic, far beyond an accepted taste.

The Hood returned to Gib to resume patrol duties, war exercises and showing the flag, this being visits to foreign countries.

On one such visit we went to Split in Jugoslavia for the young King Peter’s birthday where leave was given, and many sailors went ashore for recreation and swimming. It was whilst swimming that one of the lads dived into what looked like deep water and he struck his head on a rock which became a broken neck. After first aid he was returned to the ship for medical attention as we had a very capable medical team and equipment on board. The Hood shortly afterwards returned to Malta and our injured man, Jock, was sent to Bighi Hospital.

His damaged neck was slowly beginning to mend and we were given to understand that his neck would fully recover. In the meantime Hood had resumed her normal pattern of work and on one occasion of returning to Malta I was detailed with three other stokers to stretcher a sick stoker to the hospital. We were crossing between the wards when one of the stokers noticed Jock walking around which was a good sign. The stoker called out to Jock who on hearing a familiar voice turned his head sharply and on doing so broke his neck again. Later we were told that he had been returned to England for more specialist care, I never knew what happened after that.

When returning to Malta from one patrol one of our signal men was taken ill with appendicitis and our surgeons had to do an emergency operation, which unfortunately was not successful, the surgeons were unable to save the signal man.

After I had completed my auxiliary course a notice was put on the regulating notice board saying that a stoker was required for the Captain’s Motor Boat. I put in my request for this position and was lucky enough to be accepted. This proved a good move in that I was classed as a special duty man and relieved of all other duties. Whenever the Captain required his boat I and the rest of the crew had to be there. Our crew consisted of a PO Seaman, a Leading Seaman, an Able Seaman and myself. The Captains I served with were Captain Pridham, Captain Walker and Captain Glennie; of these three Captain Walker I served with most. He was very energetic and given to outbursts of temper if an order was not carried out correctly, never did I fall foul to him. His nickname was Hooky because in the Great War he had lost an arm and was fitted with an artificial arm with a hook and if someone did not carry out an order correctly Hooky was liable to swing his binoculars carried on his hook in that person’s direction.

One day we had to take Hooky to a tanker anchored in the Bay. We went alongside to a Jacob’s rope ladder hanging down the tanker’s ship side. Hooky with great agility went hand over hook up the ladder on to the deck with such speed it would have put a fit man to shame. It was fantastic to watch.

Our boats crew was called away one evening to take Hooky to a large yacht in Malta harbour. When the Captain had got on board he gave the order for us to lay off, which meant that the visit would be short and we would be called alongside. We waited and waited, the coxswain keeping the boat in sight of the yacht. After several hours in which we had lost our evening meal the boat was called to pick up Hooky, who we returned to the Hood. Hooky on going up the gangway turned to the coxswain and said, ‘Coxswain I believe I have kept you waiting? Anyway it's part of your duty, Goodnight’ and that was that.

The Hood was kept on patrol and exercises and one operation we had was to do a fifteen-inch shoot at a moving target with live ammunition. The target being H.M.S. Centurion, an old battle ship that was radio controlled by H.M.S. Shikari. Her crew would take the Centurion to sea and when in the operational area the crew would be taken off and the Shikari would take over. The Hood on firing her first salvo straddled the Shikari. This would have been disastrous had the salvo hit the destroyer. Unfortunately for the Hood’s gunnery officer the Commander in Chief Mediterranean Fleet was on the Shikari to observe the action. Anyhow we carried on the action, getting several hits on the Centurion. The ships then returned to Malta our Gunnery Officer having to see the C in C Med for his excuse for the wayward first salvo.

One trip found us back in Gib and we were suddenly put on sailing orders. The Hood then proceeded into the Atlantic, up to Bilbao in Northern Spain. It would appear that a British cargo ship was trying to run the blockade and get a cargo of potatoes to Bilbao. A Franco warship was trying to intercept it. The Hood steaming at high speed arrived at the scene put herself between the Spanish warship and the cargo boat. This entailed a lot of toing and froing. At one time the Spaniard was on our port side – left – and then on our starboard side, - right -, this cause a problem on Hood as we were not fully manned. At one time the port six-inch guns were manned and when the starboard side guns were nearest the Spaniard, the gun’s crews had to cross from port to starboard. This went on for quite a time until the cargo boat got clear and everything went back to normal. Captain Potato Jones returning to England with his cargo boat and the Hood returning to Gib.

At one time the Hood did a courtesy call to Marseilles in Southern France. On going through the Gulf of Lyon we encountered the roughest sea I ever experienced in the Mediterranean. On arrival at Marseilles the Captain had to be taken ashore. This we did but on the return trip the boat’s engine packed in. After signals between the coxswain and the Hood we were eventually towed back. This stoppage of the engine caused a big flap. Engine room artificer Bill Brading, was sent to investigate and found that the engine had seized up. By this time Lieutenant Commander (E) the senior engineer had turned up and finding Bill Brading’s report ordered me to be removed from the boat immediately and put on report. A spare engine was put into the boat and another stoker took over my duties, it being assumed that I had neglected to put oil into the engine. Unknown to me Bill Brading went to see the Senior Engineer and suggested that no claim of negligence could be found until the engine had been examined. The following day I was duly presented to the Senior Engineer as a defaulter. The charge being neglect of duty and that I had failed to maintain a level of engine oil required. This I denied and the Senior Engineer asked how I could say that when the engine had seized up. I then stated to the engineer that I could bring four witnesses to state that there was the correct level of oil in the engine. The Senior asked how I could do that to which I replied that prior to anchoring four stokers doing their auxiliary course were under my instructions and each one had to check the engine level on my instructions. These four were called and stated what was said was true. The charge was dismissed and I was reinstated to the boat. It was brought to my attention afterwards that the Senior was very devious in that he knew the cause of the engine seizure was a mechanical fault and not through the lack of oil. This was found in the dismantling of the engine as soon as it was removed from the boat and the statement from the PO Coxswain that until the engine stopped there was no lack of oil pressure on the gauge in the cockpit. An episode never to be forgotten.

At a later date I was put on report for failing to supply a fire extinguisher, the Hood was on the Mole at Gib and all motor boats were moored aft of the ship. The Captain’s ship was called away to go across the harbour and while we were waiting for our PO to turn up a seaman called to me for my fire extinguisher as there was an exercise on the quarterdeck. I said to the seaman that I would not allow the fire extinguisher out of the boat for an exercise, as the boat was about to leave, by this time our PO had arrived and we went across the Harbour. On our return I was told to report to the Officer of the watch for refusing to obey an order. I was duly paraded on the quarterdeck, off cap and charged, in my defence I gave the reason for not obeying the order and the Officer of the Watch sent for the Engineer Officer in charge of boats for his opinion. He reluctantly agreed with me and the charge was dismissed. From that time on I was very wary of all officers.

Twice while in the boat’s crew I found myself in the sea. On the first occasion the Hood was at anchor at Tangiers. Our boat was lying from the port after boom and there was a big swell in the sea coming from the Atlantic. This was causing problems as our boat was being thrown against the ship’s side. The Officer of the Watch called us to take our boat to the starboard after boom on the leeside, the normal mooring for the Admiral’s barge, which was in Gib. On getting into the mooring the bow of the boat was on a running lanyard and I had secured the aft of the boat with a static rope and I was stood up rolling up the White Ensign when the boat suddenly sprang upwards and threw me into the sea. The Admiral was on the quarterdeck and shouted out to me “Don’t lose that flag!” giving no thought that I might need assistance which I did not. I managed to get to the gangway and went on board to change from my wet clothing and dry out the Ensign. The reason for the boat springing was that our boat length was 25’ and the Admiral’s barge was 35’, this made the distance between the bow rope and stern rope 10’ shorter than our boat needed so that as the long roller of the sea came in the boat was lifted up on the top of the wave and as the wave went away the boat dropped away between the two ropes which were to tight and caused the boat to spring up. Letting out the stern rope on the quarterdeck rectified this. Everything returned to normal.

My second fall into the sea was in Malta harbour on a very hot day. It was practice for us when mooring the boat on the after boom to leave by means of climbing the rope ladder onto the boom and then onto the quarter deck, but it was easiest for us to jump up onto the after wire stay gripping by our hands and swinging ourselves upwards onto the boom, a slight acrobatic move, though on this day the sun being so strong there was a haze over the wire. This gave me a false distance and as I jumped up my hands did not grasp the wire so by grasping fresh air I found myself in the water. This made me more careful afterwards.

One problem we encountered in Malta harbour was loose ropes floating around that fouled our boat propeller. This caused a large operation on board the Hood; the boat had to be lifted out of the water to clear away the rope. This entailed using the Hood’s main derrick, a large boom fitted to the aftermast and was used to lift all boats in or out of the ship. It was very labour intensive using many sailors to man the ropes that pulled the derrick round to the shipside and back again, though the hoist was mechanical. I thought of a way to save this operation which turned out to be workable. I suggested to our PO that if we went into shallow water I could get into the water and if the crew went to one side the boat would list over and I on the opposite side may be able to get at the propeller to release the rope. This proved successful and the PO got a pat on the back for saving a massive derrick operation.

On one visit to Malta we were enjoying some night leave; I had now become 20 years of age and drew my rum ration; when a strong wind, Maltese Gregale, blew up. This was so intense we could not return to the ship, we were met on the jetty by the local naval patrol and told to remain ashore. This kept us on shore for three nights, which we enjoyed. When the wind abated we returned aboard to find that the ship had been using her engines to maintain her position between her moorings. It certainly was some wind.

During one stay in Malta a cruiser came in from England with many naval cadets and midshipmen on a training cruise. These young men would be the naval officers in future years. Our motorboat was called away and we had to go to custom house to pick up a Captain and his wife, and then proceed to the cruiser as their young son was on board as a cadet. We went alongside the after gangway and the captain was piped alongside. The piping party consisting of several cadets seamen POs and seamen; the captain’s wife going up the gangway noticed her son in the piping party and to his embarrassment called out in a reasonably loud voice that everyone around could hear, ‘There’s my baby!’ I often wonder how that 17 year old felt.

On one trip back to Malta it was decided for the Hood to go into the floating dock; this would be a great achievement, as the floating dock had never accommodated such a very heavy vessel. The floating dock was lowered and the Hood was gently eased into the dock and when secured the water was pumped out of the dock and the Hood was lifted out of the water – no mean feat! As the dock lifted and the Hood was in her docking position the watch of seamen were called on deck. This sudden body of over 200 men on one side of the ship caused the Hood, who was only partly buoyant, to list one side. To prevent a near disaster the dock was flooded until buoyancy of the Hood was recovered and the list taken off. There being no further incidents the floating dock lifted the Hood out of the water and kept her there for several days while under water maintenance was done, the ship’s bottom cleaned and painted. We then undocked and went about our patrol and exercises.

The navy encouraged all types of sport and rivalry between ships of the Med fleet was no exception. On one visit to Malta the Hood played H.M.S. Barham at football, losing 7-0. On the next day Barham was leaving Malta to return to England having completed her commission in the Med. Barham left her moorings in Grand Harbour flying her paying off pennant of many yards – indicating length of ship and time spent in the Med – very impressive pennant. As Barham passed Hood in Bighi Bay it was noticed that an additional adornment was displayed on ‘B’ 15” turret; Barham had rigged a temporary mast from which was hung seven footballs, talk about rubbing it in.

During her time in the Med the engine room personnel under the watchful eye of a Chief Stoker produced a harmonica band consisting of many mouth organ specialists, the band gave concerts and even did radio broadcasts, they were very entertaining and though amateurs were very professional.

There were many sporting activities for the crew, from water sports, all athletic events, sailing or rowing competitions, name it, it was available. There were also various educational exams that could be studied for as the Hood had classroom facilities, with qualified teaching staff. It was better for junior sailors to be drafted to capital ships on their first commission, as there were more facilities available than on smaller ships. The large ships offered more chances towards promotion than the smaller ships did.

During the 1938 crisis the Hood was at Gibraltar and several foreign warships were present. Among these the German pocket battleship Deutschland, who was on non-intervention patrols. As the crisis reached a peak Deutschland sailed into the Atlantic, followed later by the Hood in what was a cat and mouse shadowing. The crisis died away and the Hood and Deutschland returned to Gib, Hood on tying up on the Mole suffered a serious accident when an after mooring wire parted causing a death of a Royal Marine and a young seaman.

Later after the burial of these two a football match was arranged between the Hood and Deutschland with the proceeds to go to the dependants of the unfortunate two. This illustrates the fellowship of the sea; one day standing by to fight to the death then later in comradeship playing a game for charity.

It is the tradition in the navy that when shipmates die, that their effects not wanted by the relatives are auctioned to the ships company, this auction will always bring in exceptional proceeds as items of uniform will go to the highest bidder who will offer a price far in excess of the articles value, all proceeds go to the nearest relative.

The Deutschland at the start of hostilities was renamed Lutzow, this was on Hitler’s orders as he did not want a ship bearing the German name lost at sea through enemy action.

One evening before I took over the Captain’s motorboat an evening duty was in the Stoker PO’s mess, to assist in setting the evening meal and cleaning up. On finishing the task Bernard the regular messman asked me if I would lend a hand rolling some leaf tobacco. The leaf tobacco purchased from the stores has to be rolled into a shape like a small rugby ball. To achieve this a piece of light canvas is laid out and the leaves of tobacco, minus their stalks, are laid onto the canvas, sprinkled with diluted rum, rolled into the canvas and sown up. Then with a long length of spun yarn suspended between two hooks, the canvas sack is rolled very tightly with turns of spun yarn compressing the sack of tobacco until it is about half its diameter. The spun yarn would remain around the sack until as such times the plug of tobacco was considered ready for use. Bernard was an expert at rolling tobacco; his services were used by the POs to do this rolling. The POs would each give Bernard some rum to go into the tobacco; Bernard would drink this and put sugary water into the leaves; I must say that I enjoyed some of the rum that night.

The stalks had to be returned to the stores as they would be made into snuff.

Bernard had been in the navy many years and was a very colourful character. His many years had spread over the 22 required for pension as he was making up for lost time in detention. He had no good conduct stripes or good conduct medal. His failing was that he liked a good night ashore and invariably broke the rules. The last time while I knew him was when he went ashore, had a good night and returned to the ship with half his beard missing on one side and half his moustache missing on the opposite side. This invoked a punishment because to grow a beard permission must be obtained from the Captain and to shave off a beard the Captain had to give permission, it was actions like this that were with Bernard during his time in the Navy.

These are some of my memories whilst I was in the Med during which time my visiting was very limited. Having spent over 2 years in the Med I visited 11 different places in 7 different countries. In Greece I went to Corfu and Argostoli; in France I visited La Rochelle, Gulf Juan and Marseilles; in Yugoslavia one trip to Split, there were two visits to Tangiers in Morocco, one visit to Oran in Algeria, several visits to Palma an island in the Balearics, plus numerous stays in Gibraltar and Malta. Not very many to the time spent in the Med, the Hood returning to Portsmouth early 1939. I’d been there, where?

On returning to Portsmouth the Hood paid off the ship’s company to RNB, though I stayed on because I had a good job. Up until August there was very little activity on the ship by the remaining crew as the ship was in dockyard hands for maintenance and some modifications. The Captain’s motor boat went into the dockyard for an over haul and until it was returned I spent my working hours helping the artificer in maintaining the other ship’s boats, this went on for several weeks until the Captain’s boat was returned then I went back to my special duties.

After coming out of dry dock the Hood was berthed at Farewell jetty and all the ships boats were moored between the ship and jetty along side the quarter deck, the ship was kept away from the jetty by large pontoons The officer of the watch instructed the coxswain of the ships launch –a large motor boat that could carry fifty or more persons – to secure the launch as it was no longer required that day, this was done .The next morning when the coxswain went to the launch it was missing this caused a flap, after a frantic search the launch was found under water on the harbour bottom. When the launch was moored it was high tide and the ships mooring wires were over head, but as the tide ebbed the heavy mooring wires landed on the launch and as the tide ebbed to its lowest the launch was totally submerged completely flooded by the weight of the wires. There was a minor salvage operation needed to recover the launch.

We left Portsmouth for Scottish waters to join up with the Home Fleet, visiting Invergordon and Scapaflow – everybody was fully expecting the war to start- the Admirals were constantly exercising the Fleet.

On one of these exercises the Hood was going out to do a full 15” gun shoot. It was decided that the main motorboats would stay in Scapa until the ship returned later in the day. This would save using the main derricks, which as I have mentioned before is a very tedious operation. However during the course of the day, War was declared and the Hood with other units of the Fleet were deployed searching for German ships and did not return to Scapa. We in our little boats were alongside the jetty and all we could do, as we did not know the situation was wait until contacted.

We spent the night on the boats and next morning went to the huts belonging to a salvage company. The salvage company was recovering ships of the German Grand Fleet scuttled by the Germans at Scapa on surrender after World War 1. We were told of the declaration of War, were given a good breakfast, a signal was sent to H.M.S. Iron Duke, a World War 1 British battleship, doing accommodation work for the Fleet as she was obsolete and not considered suitable for combat. The Ironduke sent a message to our boats to go to her for orders. The order was given that we would be accommodated aboard while the Hood was away. Iron Duke would use us as required, - I at this time was acting as coxswain for the boat, the PO and Leading Seamen were on the Hood for gunnery duties. As the evening closed the Commissioned gunner told us that buoys had been laid near the shore; we were to moor there, we must pull the mooring wire from the buoy through the bullring on the bow of the boat to the deck cleat. The bullring is a metal fitting on the very front of the boat. We thus went to our mooring, moored up, one of the Iron Duke boats taking us back to the ship.

The next morning we were returned to the boats for commencing our duties. On arrival at our boat we found the stern high in the air and the bow under the water, this happened because the mooring buoy did not have enough wire to allow for the rise or fall in the tide. The cleat had partially broken from the boat; we had to wait until the tide had receded until we could release the boat. On return to the Iron Duke we were given the job of taking the pilot and navigator of the Fleet Air Arm Walrus flying boat to and from their plane. This was a very simple task.

There was quite a problem for us Hood’s boats crew in that we had no materials for washing and only the clothes we wore, this matter was raised on the Iron Duke and although we were loaned bedding no one wanted to help us out with toiletries. In the end we were given a loan of money repayable from our pay to purchase toiletries – not very friendly people.

After three days the Hood returned and we were all glad to get aboard. The next day after our return the ship was painted and looked very smart. A captain from another ship signalled ‘I hope your gunnery is as good as your paint’ – friendly banter between captains. The Fleet was suddenly sent to sea as it was reported that German warships had been sighted. A very impressive array of ship’s sail consisting of two battle cruisers, a battle ship, one aircraft carrier, several cruisers and numerous destroyers looking for the German ships that were not there. The Fleet had been sailing some time when an air alarm was given. A solitary German plane came over the fleet, dropped a few bombs and flew away. Without any of the massive amount of aircraft guns finding the target. The Hood had one bomb land alongside that lifted all the tiles in the Stoker’s bathroom. Perhaps the paint was better than the gunnery.

The Hood in the short time since the war started was doing a lot of sea time and was under manned of Stokers. I had to help out with watch keeping; because I was required on the motor boat on arrival in harbour my watch keeping was on the plumber blocks and I could get away from there with no difficulty. This duty was carried out in four compartments aft the engine rooms, the four engine shafts passing through to the propellers. In each compartment were large bearing supporting the engine shafts, each being supplied by lubricant from the after engine room. It was my duty to visit each compartment to check the oil flow and bearing temperatures. Quite a simple exercise, the only arduous duty to open and close the water tight doors and to ascend the ladders approximately four times an hour; before a door could be opened permission had to be obtained from the bridge and the bridge informed when the doors were opened and closed. About two days before I left the Hood I had been doing this duty and we called into Greenock before going to Scapa Flow. I was told that I would be going to RNB for my POs course and would leave from Scapa.

On the Thursday on arrival at Scapa I came off watch and thought that I would spend the day getting my kit clean. When the regulating Chief Stoker told me that the Admiral had said his staff were to be excused all duties for 24 hours this meant that Jake Scott, the Admiral’s Leading Stoker had to be relieved. As my boat was not wanted I would take over the Admiral’s barge, this I did not like at Jake was never required for duties when the ship was at sea and I had just come off watch, but no argument put up by me prevailed. Fortunately I was only required for one small trip before the barge was hoisted in. I left the Hood on the Friday for the long journey to Portsmouth

To go back to my early engine room watch keeping days one watch I was employed in the after engine room looking after the steering engine and oil pump servicing the plumber blocks, when I noticed a massive depletion in the oil tank for the plumber blocks, an inspection was made in the plumber block compartments –four in number – and it was found that one of the vent taps had been left open and oil had been pumping into the bilges.

Further investigation found that with the quantity of oil lost, it would have taken several hours for the oil to be discharged through the vent, this meant that the stokers on watch over the plumber blocks had not visited the compartments as required, as the war had not started there was no need for the bridge to be informed of the opening or closing of the doors, therefore there was no record kept at that time The two stokers involved were put on charge for neglect of duty and hazarding the ship, they were given prison sentences.

The journey from Scapa began with a ferry trip to Thurso on the Scottish mainland, by train to Edinburgh, then to Kings Cross London, by tube to Waterloo and on to Portsmouth, carrying all the time my kit bag and hammock. On arrival at Waterloo I realised that I would not get to Portsmouth very early in that evening so I decided to go home to Eastleigh, arriving there in the evening. I put my bag and hammock in the left luggage office and went home until Monday, arriving in Portsmouth about 7.30am. The naval patrol gave me transport to RNB and thus ended my first ship adventure. I fully enjoyed my time spent on the Hood and though I did no boiler room work I did learn enough about engineering to carry me through the training establishment to eventually qualifying as Stoker PO.

Introduction / My Thoughts on the Royal Navy / Chapter 1 - Early Navy Days / Chapter 2 - H.M.S. Hood / Chapter 3 - Portsmouth Barracks / Chapter 4 - H.M.S Cossack / Chapter 5 - Coastal Forces / Chapter 6 - H.M.S. Skate / Chapter 7 - H.M.S. Tarbert / Chapter 8 - H.M.S. Concord